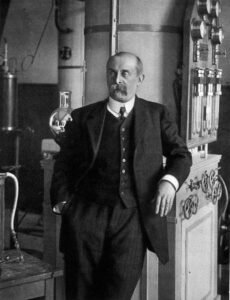

Around 1880 a French physician and biophysicist Jacques Arsene d’Arsonval had been studying medical applications for electricity.

He performed the first systematic studies in 1890 of the effect of alternating current on the body. During these studies he discovered that frequencies above 10 kHz did not cause the physiological reaction of electric shock, but warming (Kovács 1945, Ho et al. 1994, Hand 2012, D’Arsonva 2015). He developed a spark-excited resonant circuit to generate currents of 0.5-2 MHz called “D’Arsonval currents” for therapy, which became known as “D’Arsonvalization”

He also developed the three methods that have been used to apply high-frequency current to the body: contact electrodes, capacitive plates, and inductive coils (Hand 2012).

At around the same time Nikola Tesla (1891) noted the ability of high-frequency currents to produce heat in the body and suggested it’s use in medicine (Rhees 1999).

By 1900 the application of high-frequency current to the body was used experimentally to treat a wide variety of medical conditions in the new medical field of electrotherapy.

In 1899 Austrian chemist von Zaynek determined the rate of heat production in tissue as a function of frequency and current density, and first proposed using high-frequency currents for deep heating therapy (Ho et al. 1994).

In 1908 German physician Karl Franz Nagelschmidt started to use the term diathermy, and hence shortwave diathermy was born.

He performed the first extensive experiments on patients (Hand 2012). Nagelschmidt is considered the founder of the field. He wrote the first textbook (Nagelschmidt 1913) on diathermy, which revolutionized the field

(this book is now part of the historical archive and has been reproduced due to it’s scientific importance. It can be found for free in many countries archives).

Until the 1920s spark-discharge Tesla coil and Oudin coil machines were used.

These were limited to frequencies of 0.1 – 2 MHz, called “longwave” diathermy and delivered via capacitance methods.

The development of vacuum tube machines in the 1920’s allowed frequencies to be increased to 10 – 300 MHz, these were called “shortwave” diathermy.

The energy could now be applied to the body with inductive coils of wire (not needing to touch the body) as well as with capacitive plates.

In the 1930’s constant shortwave was being used in the USA for the treatment of infections (antibiotic use and safety concerns ended this).

In the 1940s microwaves were already being thought of to replace long and short wave machines. However, this did not happen.

Due to the use of radio frequencies in medicine certain radio frequencies have been reserved for medical use – that is they are not used for communications (radio, tv, mobile phone etc.)

These frequencies are listed below:

| Frequency (mhz) | Wavelength (m) |

| 13.56 (+- 6.25khz) | 22.124 |

| 27.12 (+- 160khz) | 11.062 |

| 40.68 (+- 20khz) | 7.375 |

As can be seen the 27.12 frequency has the highest allowable range and hence became the most popular.

Today, constant shortwave is not used as frequently as pulsed shortwave (due to the rapid heating effects and discomfort). Pulsed shortwave machines have continued to be used in medicine around the world where as constant shortwave, long wave and microwaves are only used in limited cases.

In their most recent iterations most machines are pulsed.

These machines are known as:

- Pulsed electromagnetic field therapy (PEMFT, or PEMF therapy),

- Low field magnetic stimulation (LFMS)

In 2007 the FDA had approved several such devices (Marcov 2007) for non union bony fractures.

However, just like any other therapy, by 2013 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned a manufacturer for promoting the device for unapproved uses such as cerebral palsy and spinal cord injury (“Warning Letters – Curatronic Ltd. 1/9/13”. www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018)

And so the history of shortwave continues…